By Melody Hsu, intern Asian Department Rijksmuseum

The Rijksmuseum Research Library and Study Room Prints & Drawings are host to national and international researchers who are working with the collections. One of these researchers is Melody Hsu, who frequently visited us as an intern at the Rijksmuseum Asian Department. Last year during our annual Speeddate event in October 2023, Melody did a fascinating talk on four Dutch woodblock replicas of Chinese originals that are part of the Rijksmuseum Print Room collection. In this article, she shares some of her findings on transcultural imagery in the case of Olfert Dapper’s printmaking.

Olfert Dapper’s (1636-1689) Gedenkwaerdig bedryf der Nederlandsche Oost-Indische maetschappye…, published in 1670 by Jacob van Meurs (1619-1679) in Amsterdam, exemplifies the city’s burgeoning era as a printmaking and publishing hub.[1] Lavish illustrated travelogue books based on accounts from the Dutch East India Company’s missions to non-European lands, which served as the 17th-century version of fancy coffee table books, captivated the growing literate middle class and educated elites with their focus on scientific exploration, curious knowledge, and exotic wonders.[2] The Rijksmuseum holds a set of four loose-leaf copperplate engravings replicating Chinese Buddhist woodcuts. They are featured as printed illustrations in Dapper’s book chapter on Chinese religion.

-continued below-

Figure 1. Copperplate Engraved Illustration annotated with no.1. Photo from Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. RP-P-1985-401. Loose leaf, 279mm x 449mm – http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.421047

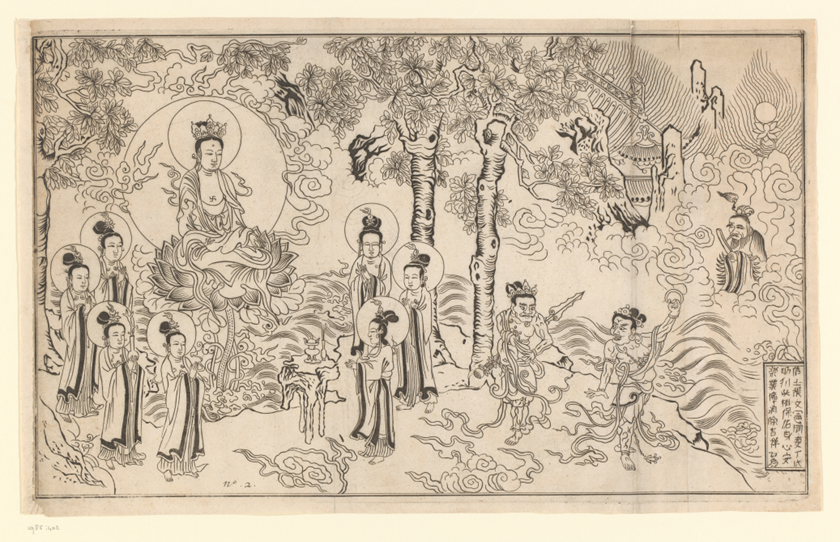

Figure 2. Copperplate Engraved Illustration annotated with no.2. Photo from Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. RP-P-1985-402. Loose leaf, 279mm x 449mm – http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.421047

Figure 3. Copperplate Engraved Illustration annotated with no.3. Photo from Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. RP-P-1985-403. Loose leaf, 279mm x 449mm – http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.421047

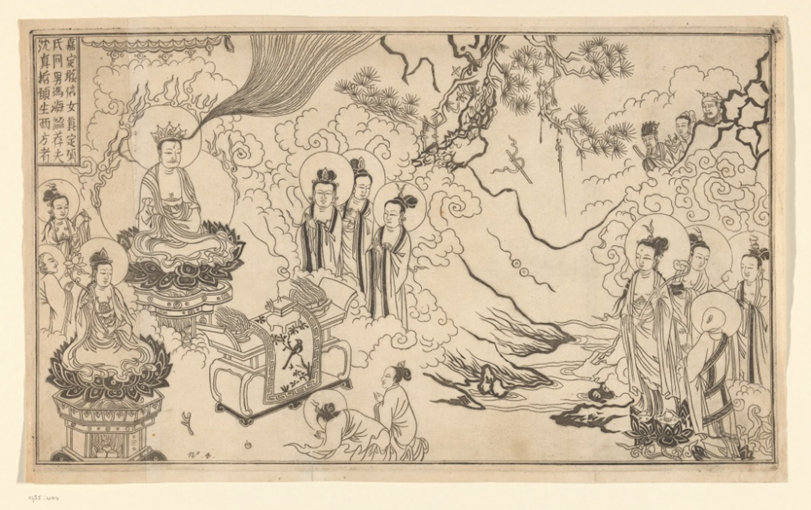

Figure 4. Copperplate Engraved Illustration annotated with no.4 Photo from Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. RP-P-1985-404. Loose leaf, 279mm x 449mm – http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.421047

The intriguing aspect of these engravings lies in the unknown Dutch engraver’s successful attempt to replicate actual Chinese Buddhist woodcuts, despite some errors such as the radiant aura of light emitting from Buddha’s crown instead of his forehead, inverse Chinese characters, and mirrored compositions. These errors are not surprising; they occurred simply because the Dutch probably did not fully understand what they were seeing while replicating. They were attempting to make the unfamiliar familiar through the process of replication, and during the printing process of copperplate engravings, naturally, mirrored scenes were generated. While Dapper’s Eurocentric distorted narratives are inaccurate, the engravings closely replicate traditional Chinese Buddhist frontispieces, such as those found in the Avatamsaka Sutra.[1] The frontispiece typically represents Buddha and Bodhisattvas in scenes of teaching or spiritual significance.[2] By analyzing visual evidence, it is clear they were likely based on manuscripts sponsored by private individuals to accumulate merits for themselves or on behalf of their loved ones, such as family members. For example, the fourth engraving in the series includes a caption – a donor colophon – indicating a devout female follower from the Xiang family and her husband Feng Hai are praying for a deceased man named Shen Zhangzhe, hoping for his rebirth in Western Paradise.[3] The two kneeling figures in front of the altar may be identified as the donors.

These prints are a product of transcultural interaction, showcasing how the Dutch sourced, imitated, and reproduced Chinese imagery and knowledge, driven by a fascination with the exotic Far East and their Eurocentric colonial ambitions. These works navigate the delicate balance between cultural appreciation and appropriation, treading the fine line between admiration and misrepresentation. Hence, these engravings represent not mere reproductions but a transformative process that yields a new hybrid form of knowledge. Reproduced, transformed, and repropagated by the Dutch, these frontispieces become visual spectacles in a Dutch historical book, serving European curiosity and constructing a visual “authentic” understanding of China beyond what words can entail. These engravings from van Meurs’ workshop, along with the biased narratives written by Dapper – the book was translated into English and German in 1671, were perceived as factual and ‘truthful’ accounts by European audiences. They were collected as encyclopedic and historical books in both private and public European collections, and the engraved illustrations were adapted into designs for Delftware.

Figure 5: The adaptation of the Buddha and the two kneeling figures into Delftwares. Photo from Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. BK-NM-12400-445 and BK-1968-141.

These four copperplate engravings are now displayed at the Asian Pavilion for a small exhibition Chinese Religion Through Dutch Eyes on view until October 2024. This exhibit spotlights 17th-century prints published in Amsterdam, focusing on how the Dutch envisioned Chinese religious culture. The selected prints are not just artistic representations; they are also historical documents that show how cultures can interpret and sometimes misinterpret each other. These works were often copied and modified from one another, some directly inspired by Chinese originals, others by existing Eurocentric narratives and imagined images that were already circulated and known within the Dutch Republic. The opportunity to curate this exhibition is a highlight of my internship. It has been made possible thanks to the mentorship of Dr. Jan van Campen, the curator of Asian Export Art, and Dr. Ching Ling Wang, the Curator of Chinese Art, and the Rijksmuseum Research Library and Print Room team.

Under the supervision of Dr. Elmer Kolfin of the University of Amsterdam, I am currently working on my master’s thesis Transcultural Replicas: Printing Chinese Religion in Amsterdam, in which the engraved illustrations replicating from Chinese Buddhist originals serve as the main case study. Modern scholarship often overlooks these engravings, instead focusing on broader publishing phenomena or more renowned works by figures like Kircher and Nieuhof. My research addresses this oversight, aiming to clarify continuing misunderstandings about the content that stems from early modern Eurocentric perspectives and to uncover the creation processes, material and intellectual itineraries, and their alignment with traditional Chinese iconography. By challenging prevailing narratives, my research seeks to deepen our understanding of Asian-European transcultural and transregional exchanges and emphasizes the importance of reevaluating how these historical artworks are interpreted and valued in contemporary scholarship.

[1]. Susan Huang, “Lecture Dr. Shin-shan Susan Huang: The Dynamic Spread of Buddhist Print Culture in China and Beyond” (Live lecture, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, April 19, 2024).

[2]. The forthcoming book by Shin-shan Susan Huang, The Dynamic Spread of Buddhist Print Culture, promises to shed light on the subject by exploring Buddhist print culture in China and its influence beyond its borders. Huang’s research, which positions these woodcuts as dynamic elements of cultural exchange rather than static artifacts, provides the contextual backdrop necessary to reassess the engravings in Dapper’s book. Huang demonstrates these adaptations were modeled on Chinese Buddhist frontispieces from the Avatamsaka Sutra, printed in Suzhou from the late sixteenth to the seventeenth century, showcasing the intricate interplay between Chinese and European printmaking traditions.

[3]. Olfert Dapper, Gedenkwaerdig bedryf der Nederlandsche Oost-Indische Maetschappye op de kuste en in het keizerrijk van Taising of Sina, 1670

Rijksmuseum Research Library – 300 B 12 – https://library.rijksmuseum.nl/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=53521

[1]. Olfert Dapper, Gedenkwaerdig bedryf der Nederlandsche Oost-Indische Maetschappye, op de kuste en in het keizerrijk van Taising of Sina…. (Amsterdam: Jacob van Meurs, 1670)

Rijksmuseum Research Library – 300 B 12 – https://library.rijksmuseum.nl/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=53521

[2]. Benjamin Schmidt, Inventing Exoticism: Geography, Globalism, and Europe’s Early Modern World (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015)

Rijksmuseum Research Library – 728 D 6 – https://library.rijksmuseum.nl/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=242973